Days of Punk

| Fashion

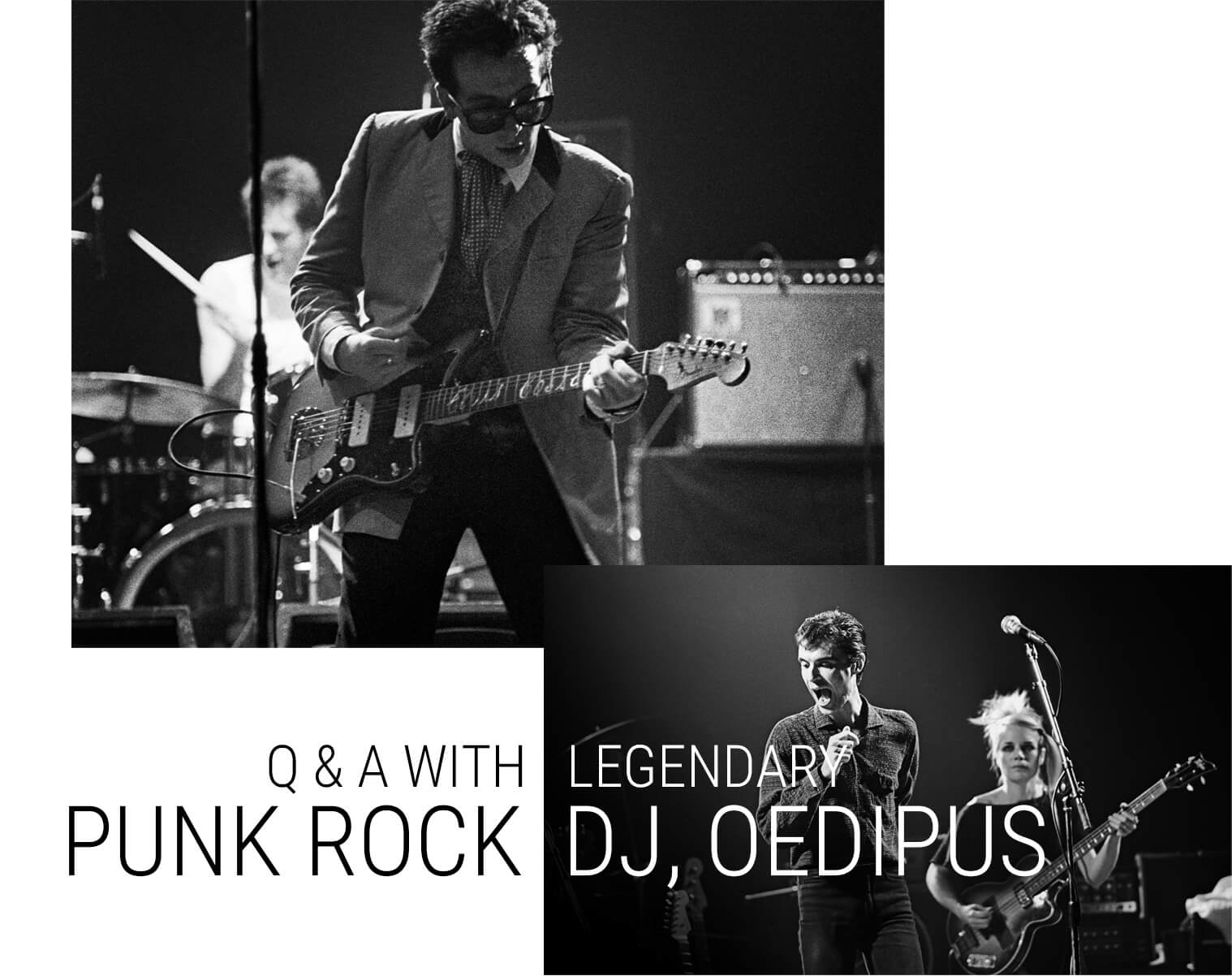

Q & A with Legendary Punk Rock Dj, Oedipus

Posted by Michael Grecco

If you know anything about the Boston punk scene, you’ve probably heard of Oedipus. As the mind behind the nation’s very first punk rock radio show, Oedipus had a massive impact on the genre at large. He was instrumental in spreading the punk rock gospel, and probably deserves credit for launching more than a few careers. We at Days of Punk were lucky enough to snag an interview with him, so read on to find out what a punk legend has to say about rock, radio, and the spirit of rebellion.

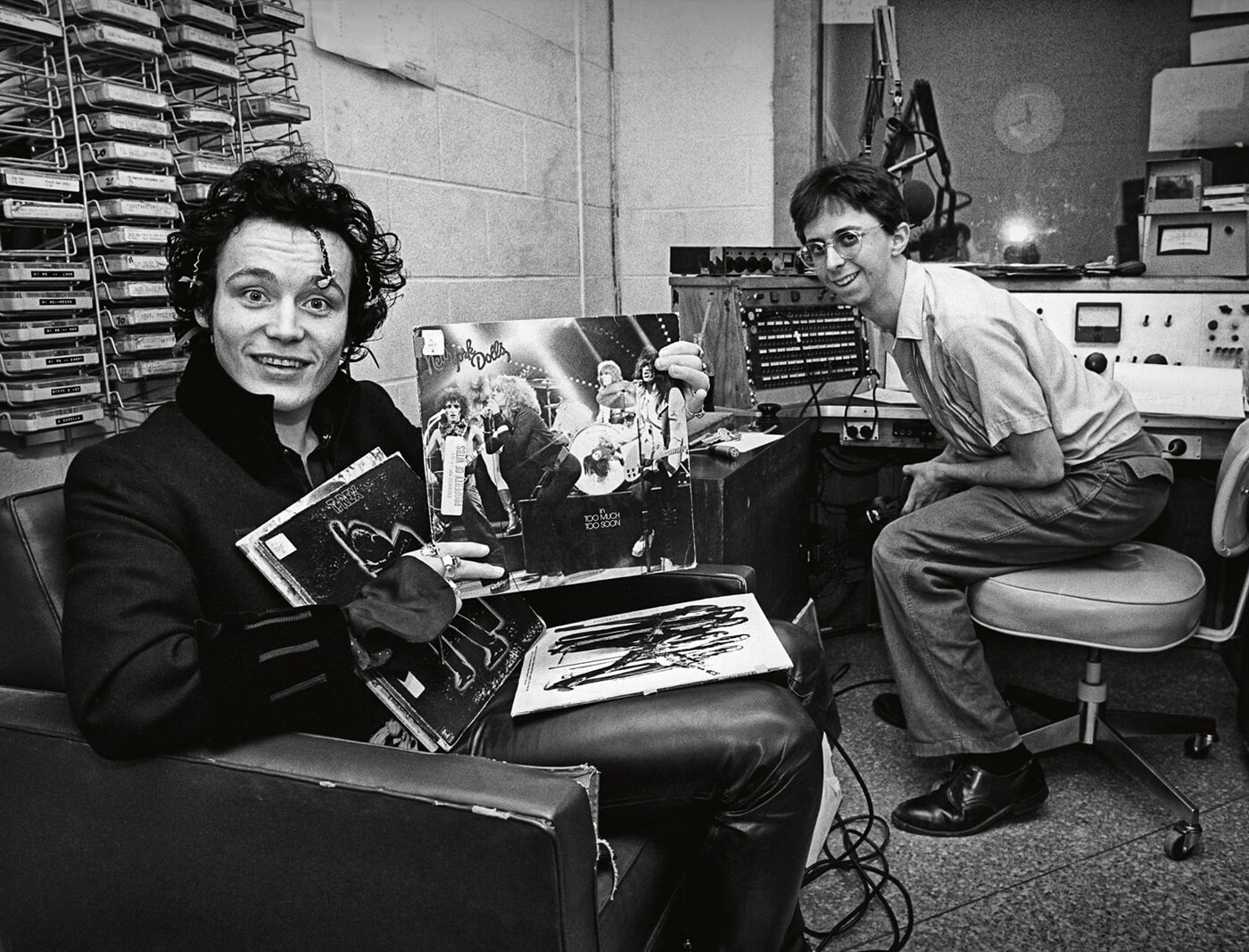

Oedipus (second from the left) with Adam Ant and band in 1981

Q: Were you really into music as a kid, or did that passion develop later on?

A: I’ve always loved music. I loved listening to the radio as a kid. My first favorite artist was probably Stevie Wonder, though I also enjoyed The Imperials, The Supremes, The Temptations—I listened to a lot of Motown.

Q: What was the first album you ever bought?

A: It was “Are You Experienced” by Jimi Hendrix.

Q: How did you end up in Boston?

A: After I left Cleveland, I traveled the world for a while. At some point, a friend who I’d met on a kibbutz told me, “You know, I think Boston is your kind of town.” So, when I was ready to be done gallivanting, I showed up in Boston with nothing but a knapsack and a guitar. I lived in a beautiful house—an old brownstone—with a group of real artistic types. One of my roommates, J.J., formed DMZ, which was an early punk band that was actually signed by Sire Records, and they would practice in the basement. My rent was sixty two dollars and fifty cents; between that and food stamps, I was able to survive.

Q: How did you get started in radio?

A: When I was first in Boston, I had a lot of different temp jobs. One day, I heard the morning man at WBCN needed a writer. He was legendary. His name was Charles Laquidara, and he hosted The Big Mattress, which was exceedingly popular, everyone listened to it. I was doing temp work at a dental clinic at the time, and I just walked out and said “later!”

I went over to the radio station and asked to meet with Charles Laquidara. He came out about an hour later and I said “Hello Charles, my name’s Oeddie, and you can’t spell it. I’m your new writer.” Now, he sort of prided himself on his grammatical aptitude, but of course he couldn’t spell it, because there was a silent O.

So, he said “Well, there’s no money, but there might be concert tickets, maybe some albums…” and he took me around and said to everyone, “This is my new writer, Oeddie. I bet you ten bucks you can’t spell his name!” So, that was Charles, and that’s how I got started in radio.

Q: Where were you first exposed to punk rock, and how did it become your career?

A: When I worked for Charles, I would stay up all night, because he was the morning man, and he started at 6 AM. I certainly wasn’t going to go to bed early—not as a young man—so I’d stay up all night hanging out with the overnight DJ and writing for Charles. One day, the news director said, “Listen, Oedipus, you get around town a lot; why don’t you start reporting on what’s going on at night?” So, I started hanging around at various clubs and venues and I came upon this kind of alternative rock scene that was starting to develop.

At the time, Boston’s general music taste was very blues based. The radio station had kind of a hippie energy, and played a lot of Grateful Dead and Allman Brothers. They would do live broadcasts from James Taylor’s house in Martha’s Vineyard. Now there’s nothing wrong with any of that, but I liked things with more excitement. I needed passion, and the DIY do-it-yourself energy that was happening in the clubs was what I was looking for.

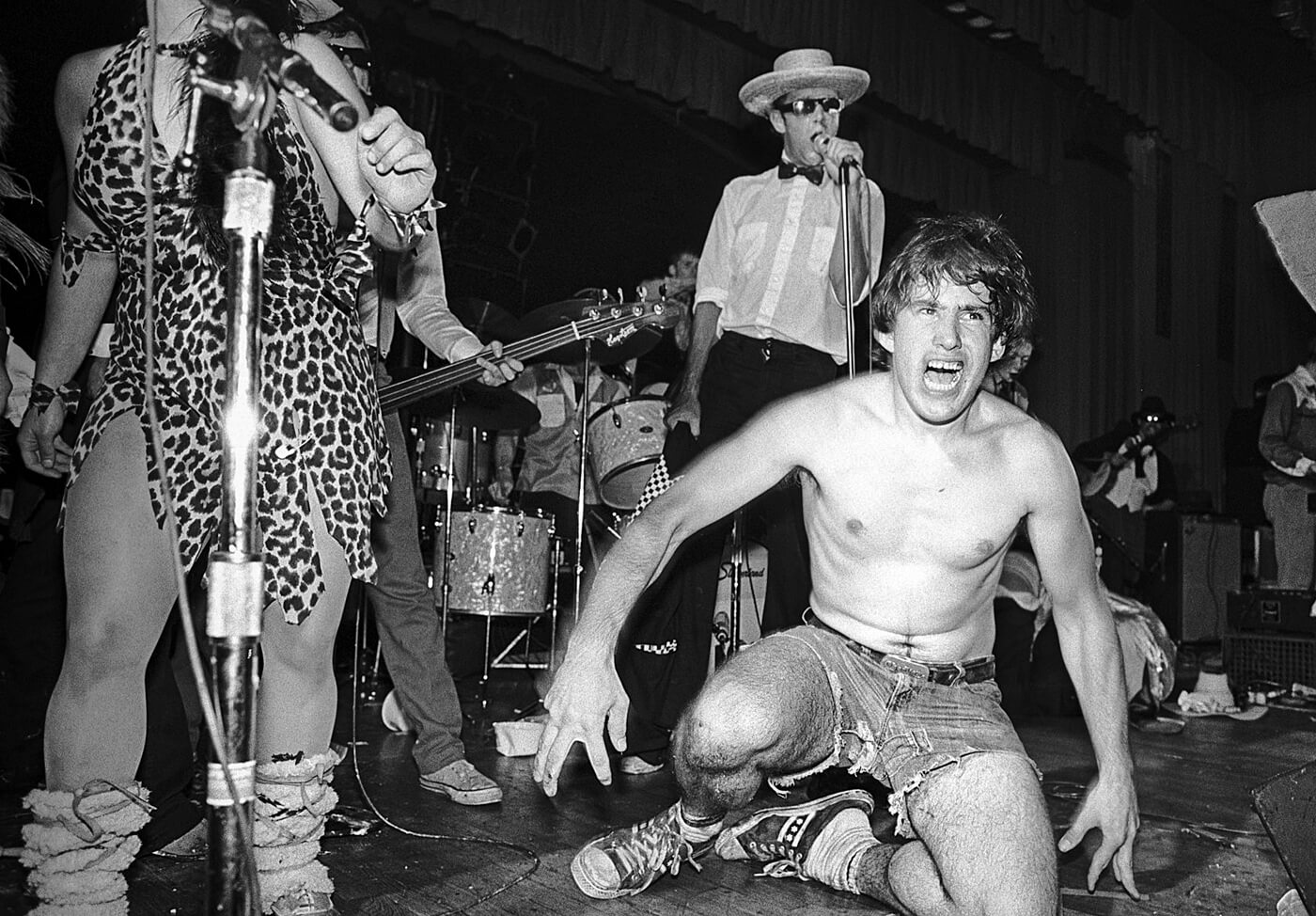

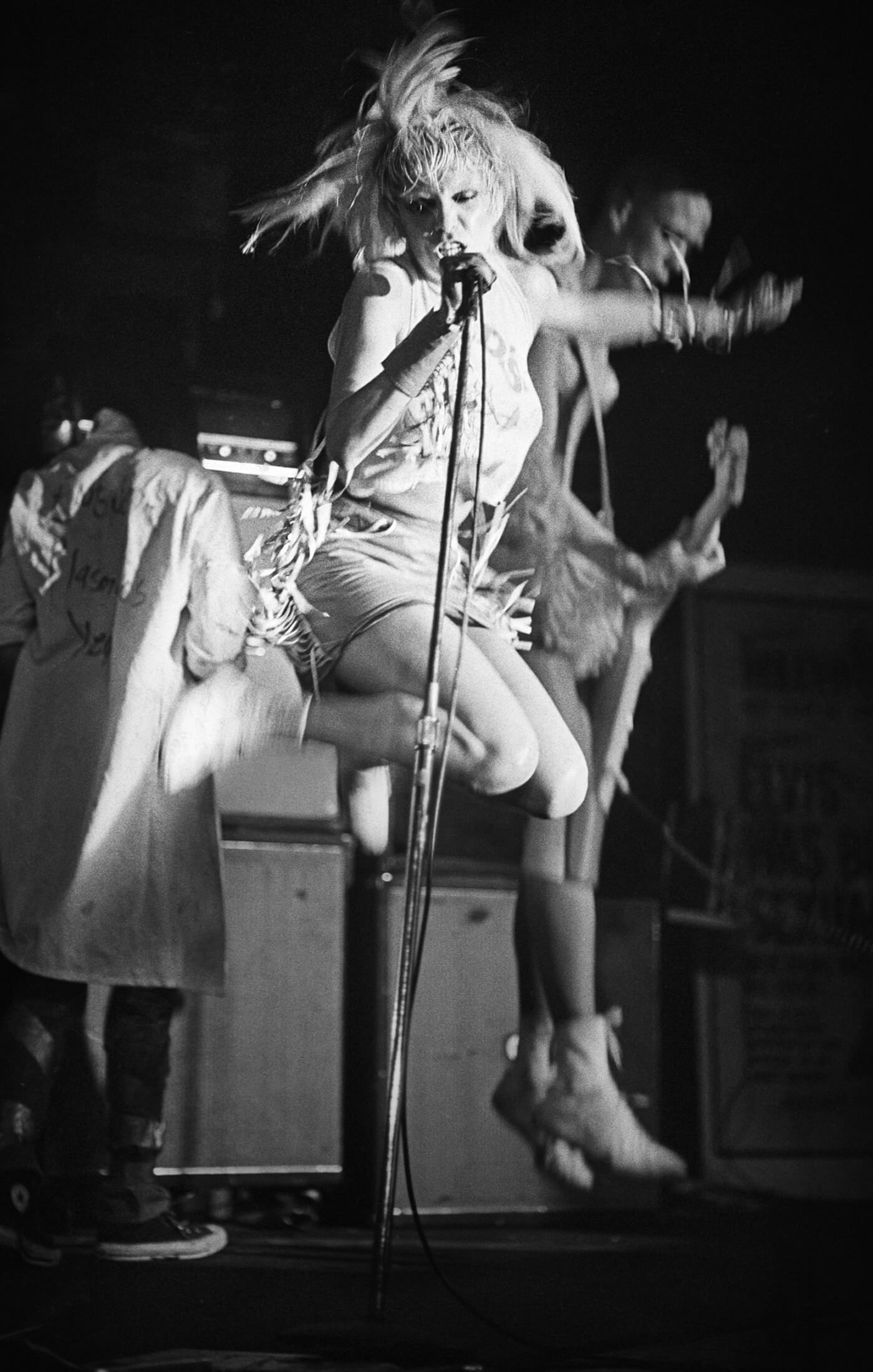

This music was coming out of the clubs, and it didn’t sound like the music that was on the radio. It was intense, and powerful, and it wasn’t being played anywhere. You couldn’t just hear this music; people had to press their own singles, because record labels weren’t signing these bands. These were the early days of Patti Smith and Television and Willie “Loco” Alexander, and I gathered this music (which you couldn’t hear anywhere) and went over to the MIT radio station—which is run by students and community members—and started playing it. It developed a following—a big following! And the show started to grow.

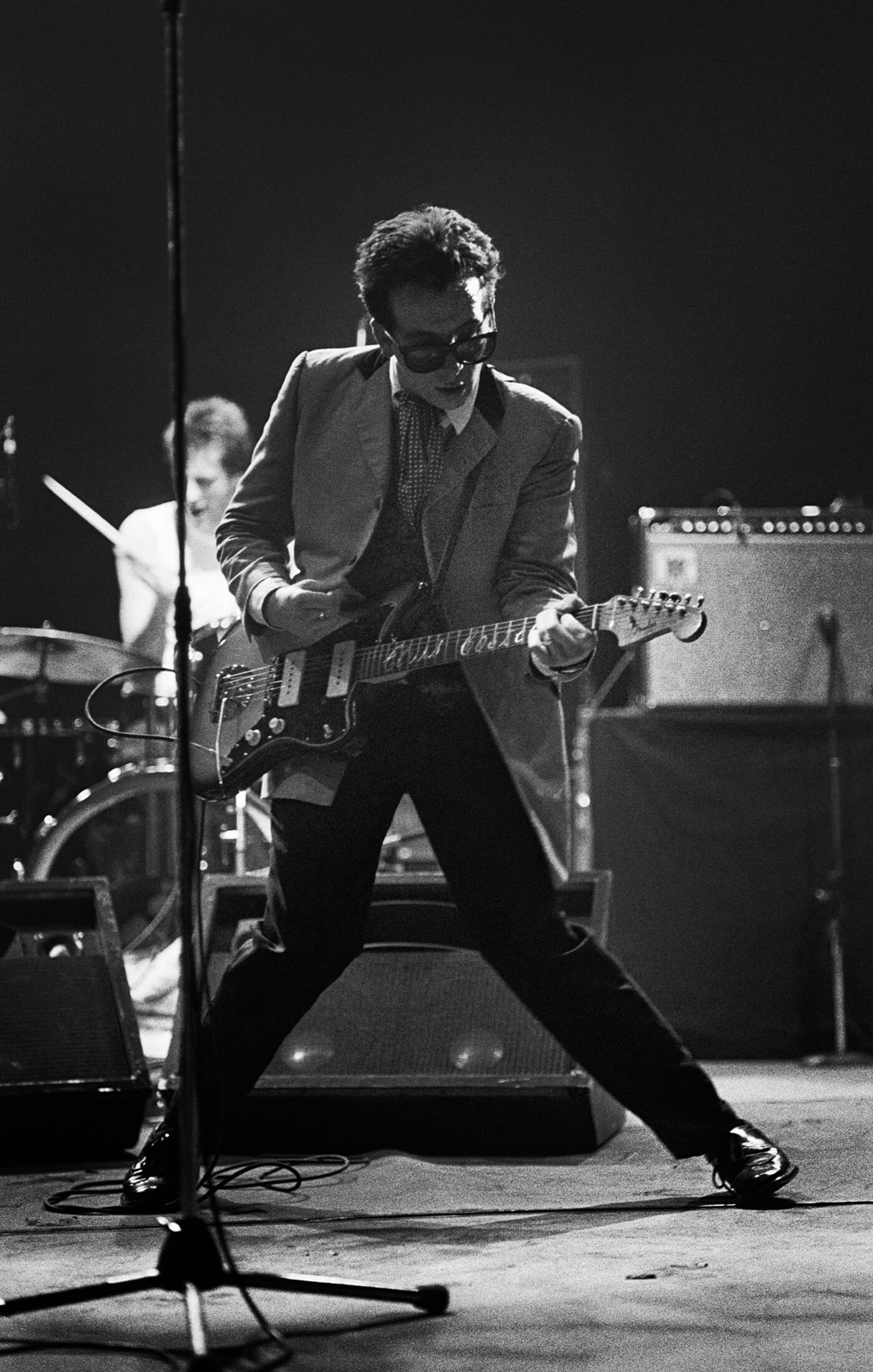

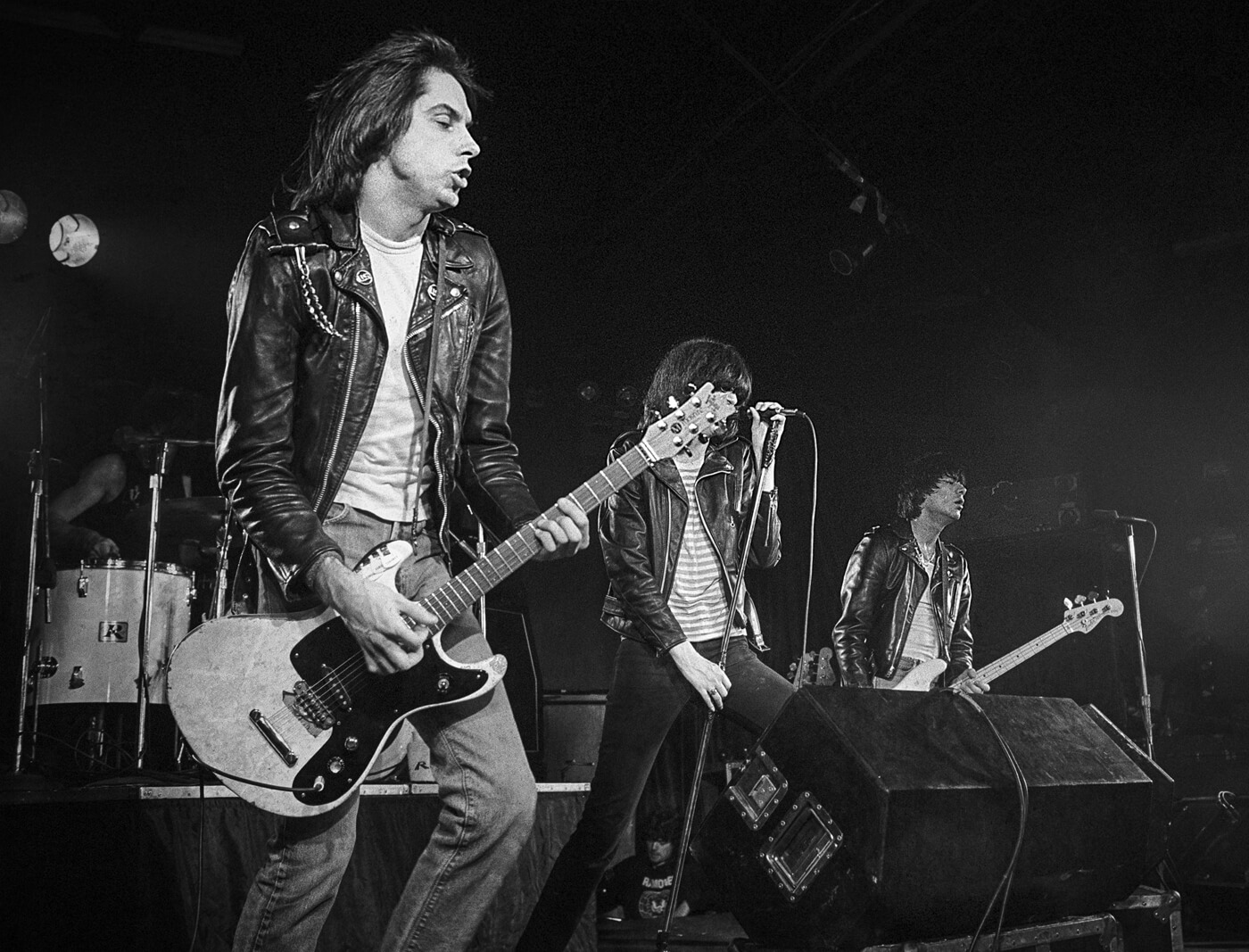

All four Ramones came down to our studio in the basement of MIT and did their first radio interview ever. I interviewed Elvis Costello, Suicide, Talking Heads when there were still only three members; Jerry Harrison hadn’t even joined yet. I had essentially started the first punk rock radio show in the country. Eventually, the big rock station, WBCN, asked me to do a show overnight, playing punk music, because it was getting so popular over at the MIT station. So, I became a full time DJ, and in 1981, I became the program director at WBCN—a position I held for over twenty years.

Q: How would you describe the Boston punk scene of the 70s and 80s?

A: It was our scene that we created. These were the days when people had fanzines; people started pressing their own singles; bands would come up from CBGB and play multiple nights at the Rat because we were receptive to this music and a lot of towns weren’t. I would dye my hair red or green or purple—now today, that’s no big deal, but back then, nobody had colored hair! And we got tattoos and we got piercings and we wore leather jackets. That all sounds cliche now, but then, nobody did it! We were the rebels, and that’s why that music was inspirational to us—because it spoke to us. We had to be somewhere in fifteen minutes; we didn’t have time for a fifteen minute guitar solo, we wanted three minutes of truth, and that’s what punk rock offered.

Q: Over the years, you’ve interviewed countless punk rock icons. What was your most memorable interview?

A: I was supposed to interview The Clash in 79. To me, The Clash was the most important band of all. They were the only band that mattered. They were passionate, they were intense, and they were political—which I loved. So it was March of 79, and I was the evening host from 10-2 on WBCN. The radio station had just been bought by new owners. We had a very strong labor union, and they figured they could break the union by firing half the staff. So, they fired us, and the whole station went on strike. Since I’d been fired, I didn’t get to do the interview, but that night, at Harvard Square Theater, Joe Strummer dedicated a song to me.

We did eventually win the strike, and in the fall of that year, The Clash came back to play Boston again. After their show, The Clash came to the radio station to be guest DJs. They started spinning records and taking calls. So they’re choosing songs, they’re playing “Okie from Muskogee”, they’re talking to listeners, and one person calls and says “You know, you guys are pretty good, but you’re nothing like Elvis Costello.” And they start swearing at each other, going “fuck you this” and “fuck you that” and this is all on the air! The interview ends with YMCA. It’s a big sing along to YMCA, and over the top of it, you hear Mick Jones going “Call the t.v. station and tell them you want to see The Clash on Saturday Night Live!” They walked out of the station singing YMCA, and it was one of those great classic interviews that can never ever be duplicated, which is just absolutely magical. It’s why I’m in music.

Q: What are the biggest changes you’ve seen in the radio industry over the decades?

A: The Telecommunications Act of 1996 basically ruined radio. It allowed corporations to own more than one radio station in a town. So now you’ve got companies like iHeart that own thousands of radio stations, and for the most part, they’re all centrally programmed. And at many of them, the DJs are also centrally programmed. One DJ can voice track multiple stations, and they can do it in a few hours because you only have to do four breaks an hour and just plug in each local radio station’s info. It ruined the local nature of radio. Without that, radio becomes generic. It’s no longer a community like it once was.

I was on the air when John Lennon was assassinated. An intern came in with something from the teletype, and she goes “Look, read this.” I was playing something, and I just stopped the song, and read it. I remember thinking, “there’s no place for commerce here, this is just too tragic,” so we stopped with our regular programming and we started playing Beatles songs. Then the musicians started calling in to the station, and then they came up and they started pulling up their instruments, and that’s the immediacy of radio. When 9/11 happened, we were able to cease commerce, and open the phone lines for people to call in and cry and scream and mourn together, and that’s the beauty of radio: it’s immediate. And we’re losing that. We don’t have that immediacy anymore, because everything’s so pre-programmed. I still have hope that one day the inmates will take over the asylum once again and we’ll return to making radio a community.

Q: What are you up to these days?

A: I’m still addicted to new music; that’s what I’ve always loved, that’s what I’ve always championed. I have a website called The Oedipus Project where I curate new music. I just do it as a labor of love now. It’s funny; I started as a volunteer, and I’m still a volunteer! But I’ve had a great career in between. I have my new music show on Saturday mornings from 10-12 on Indie617, where I play music that I don’t hear on the radio anywhere. I still find the gems, and people still trust my taste like in the days when I was playing The Police and The Ramones. There’s so much music people don’t know, and there’s always more to find!

Q: Do you have any artist recommendations for our readers?

A: I have a lot of recommendations! Nightjacket, Arlo Parks, Men I Trust, Yaeji, and U.S. Girls are all great. Sault is a British music collective doing some really cool things. Altın Gün, the Turkish psychedelic rock band, is excellent, as is the indie rock supergroup, Boygenius. I love Holly Brewer—the singer from upstate Vermont—and I’m very fond of a woman named Tara MacLean out of Canada.

Want to get up close and personal with the artists Oedipus championed? Check out photographer Michael Grecco’s incredible catalog of punk rock prints, or order a copy of his book, Punk, Post Punk, New Wave: Onstage, Backstage, and In Your Face, today.