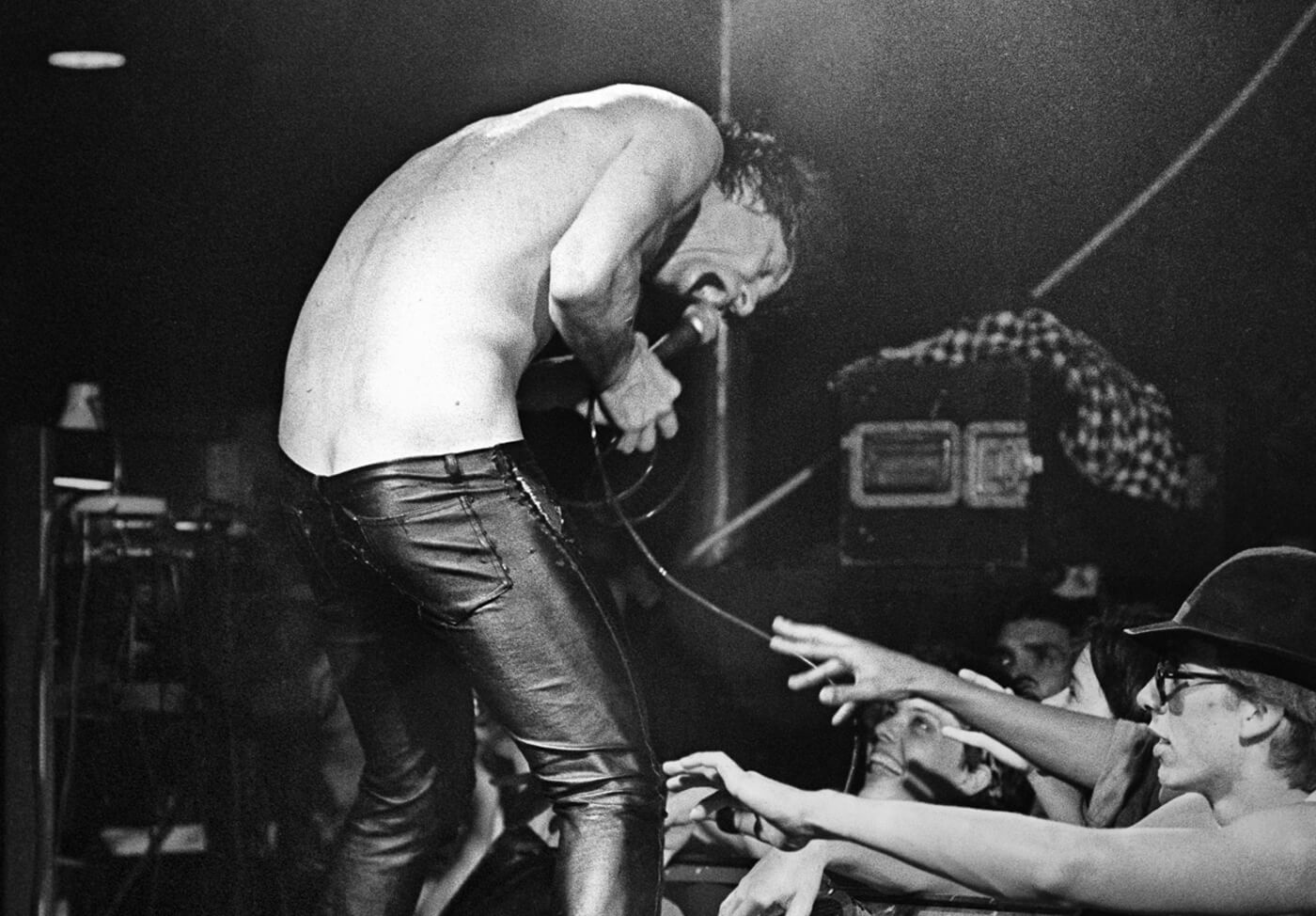

Days of Punk

| Fashion

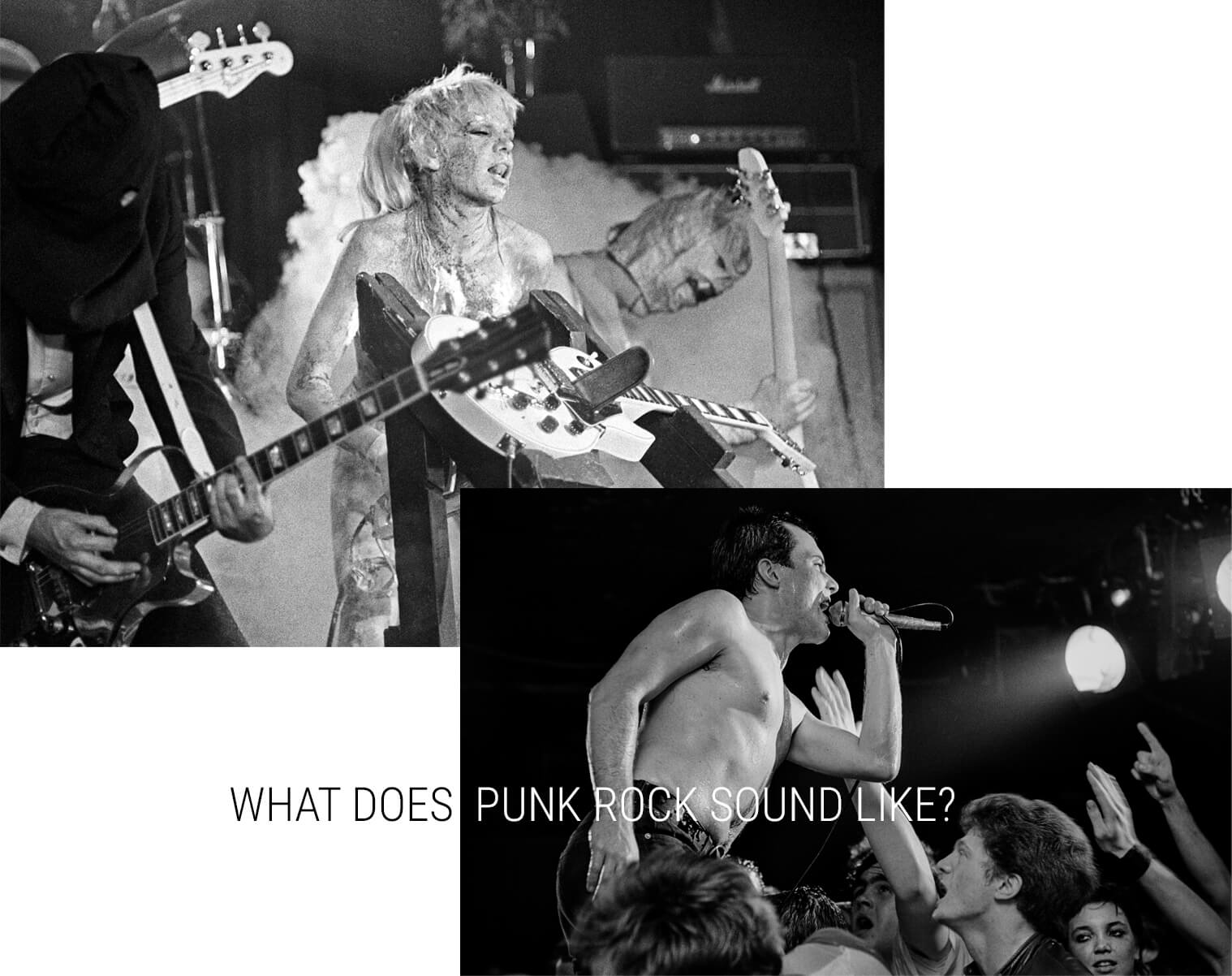

What Does Punk Rock Sound Like?

Posted by Michael Grecco

When you ask the question: “what does punk rock sound like?” you typically receive some variation on one of two answers.

Answer A is simplistic and straightforward: “Fast and loud!”

Answer B — which is more nuanced but less helpful — goes something like this: “Punk rock is an incredibly diverse genre; to accurately boil it down to a few basic sonic elements is very difficult.”

While both of these answers have merit, I find neither particularly satisfying. It’s true that most punk rock songs are “fast and loud,” but there’s a lot more to it than that. It’s also true that punk rock is a broad and varied genre. However, there are several distinct musical elements that appear time and time again; especially if you’re focusing on classic punk rock and omitting its many subgenres.

So, what does punk rock sound like? Let’s talk music theory!

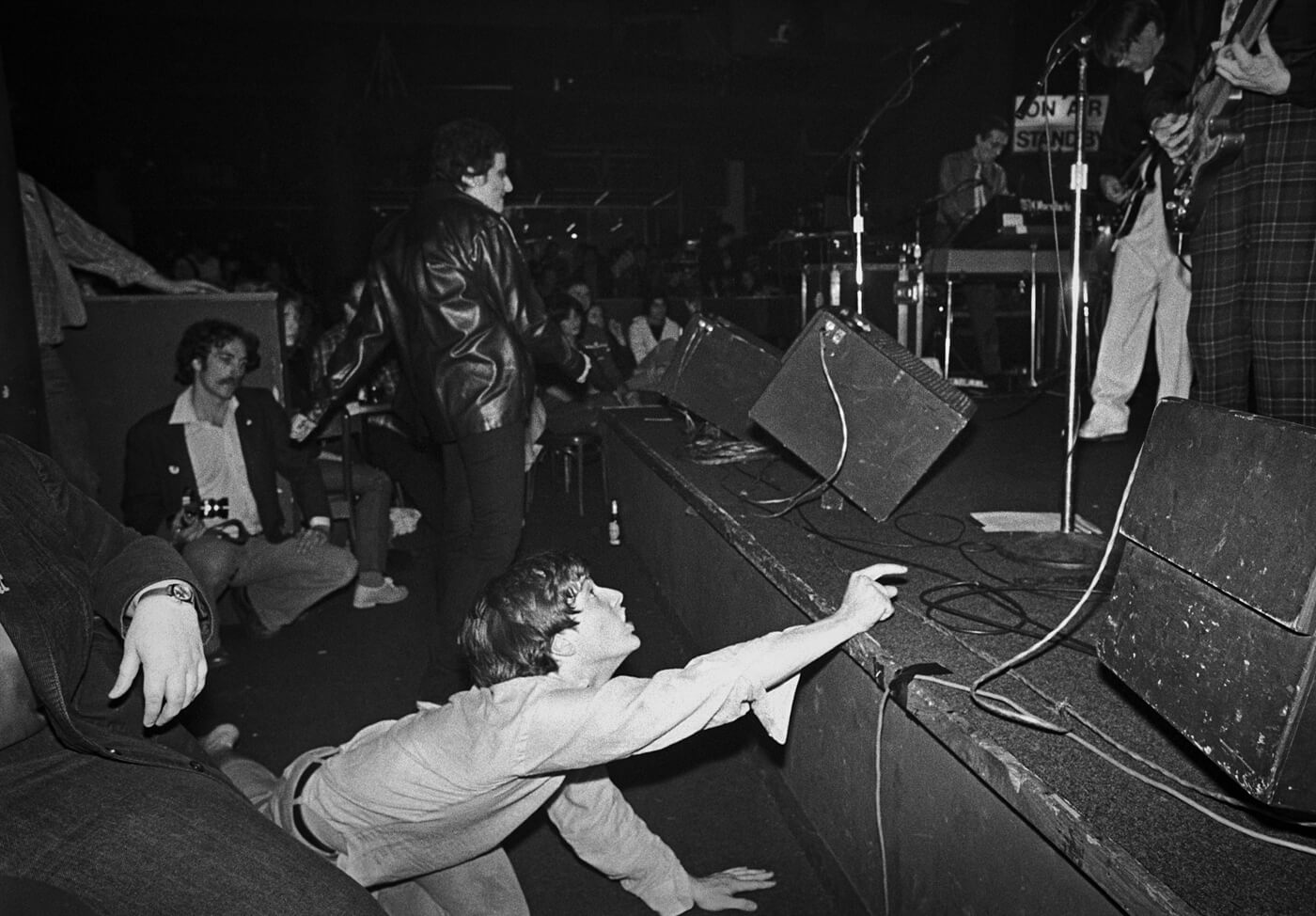

If you want to break down the sound of a genre, taking a look at instrumentation is a solid place to start. Most punk rock bands of the 70s and early 80s had a guitarist, a bass player, and a drummer. No frills, just the necessities — that was the punk rock philosophy on the matter of instruments.

It’s hard to know whether this barebones approach was born from the punk love of authenticity and distaste for excess, or from the fact that many punk rockers weren’t trained musicians and needed to keep it simple. I’d guess it’s a little of column A and a little of column B. Either way, it’s safe to say that the guitar/bass/drum combination is a hallmark of the punk rock sound.

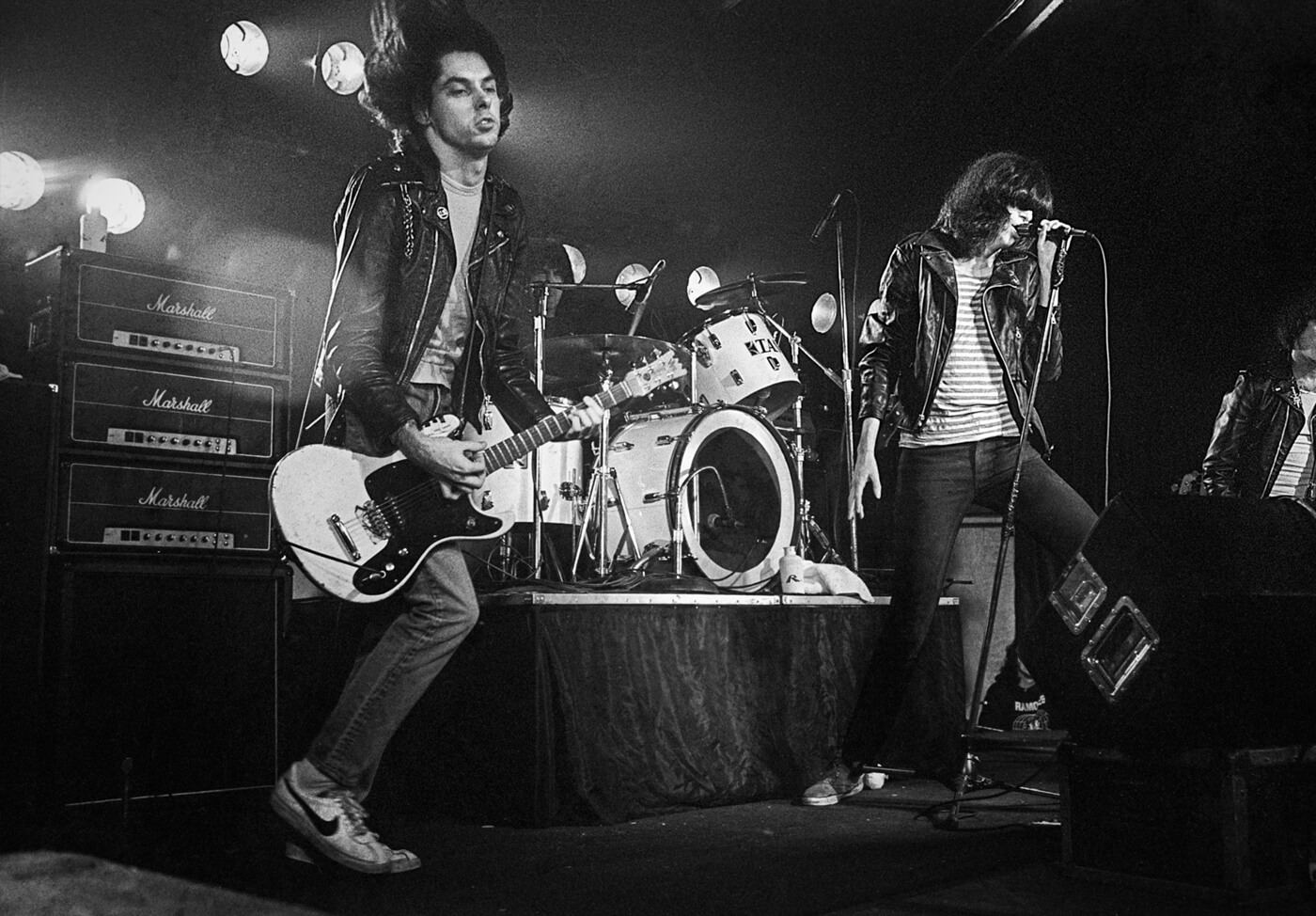

Consistent instrumentation isn’t the only punk rock throughline; listen to bands like the Ramones, the Stooges, the Sex Pistols, and you’ll start to notice a handful of other similarities. Tempo, meter, and timbre are a few of the most obvious.

In terms of tempo, punk rock music sets a punishing pace. A lot of it clocks in somewhere between 150 bpm and 180 bpm, dancing between allegro and presto (or in layman’s terms, fast and very fast). This contributes to the urgent, driving quality often associated with the genre.

As far as meter’s concerned, most early punk rock songs stick to good ol’ 4/4, the favored time signature of rock and roll. Consequently, classics like “Blitzkrieg Bop” and “Holiday in Cambodia” come off sounding like intense, chaotic marches.

Timbre is perhaps the most overt indicator of early punk rock. If you’re unfamiliar, timbre is essentially a description of sound quality (think sweet and clear for a flute or bright and brassy for a trumpet). Throw on a song by the Cramps, the Damned, X-Ray Spex, or any of their contemporaries; you’ll immediately recognize that quintessential punk rock sound. It’s harsh, strident, raucous, buzzing. The genre’s typical timbre could hardly be described as mellifluous, but it is potent and compelling.

Another notable punk rock quirk is frequent use of sprechgesang. Sprechgesang is a vocal style that falls somewhere between talking and singing; it’s a technique that’s been favored by punk rockers since the dawn of the genre. You can hear sprechgesang in “I Wanna Be Your Dog” by the Stooges, “Anarchy in the UK” by the Sex Pistols, “Gloria” by Patti Smith, “I Heard it Through the Grapevine” by the Slits, “Should I Stay or Should I Go” by The Clash, and myriad other punk rock classics.

I’m sure we could go on for ages connecting the musical dots between various punk rock songs — chasing that question of punk rock sound in circles until reaching a conclusion (or quitting in confusion) — but let’s leave it at this for now: punk rock sounds like revelry and revolution, chaos and catharsis, and above all, authenticity.

Want to know more about the ins and outs of the punk rock scene? Check out photographer Michael Grecco’s history of punk rock book, “Punk, Post Punk, New Wave: Onstage, Backstage, and In Your Face” to get up close and personal with legends like the Ramones, the Sex Pistols, the Cramps, and more.