Days of Punk

| Fashion

Punk Rock Continued: The History of New Wave

Posted by Michael Grecco

Punk Rock Continued: The History of New Wave

You’ve heard of new wave — that nebulous musical term that’s been bandied about haphazardly for the last half century — but do you really know what it is, or where it came from?

Over the years, the “new wave” designation has been thrust upon many an artist of many an ilk, which has resulted in some definitional confusion. However, if you start at its roots, and trace the branches from there, new wave begins to lose some of its ambiguity.

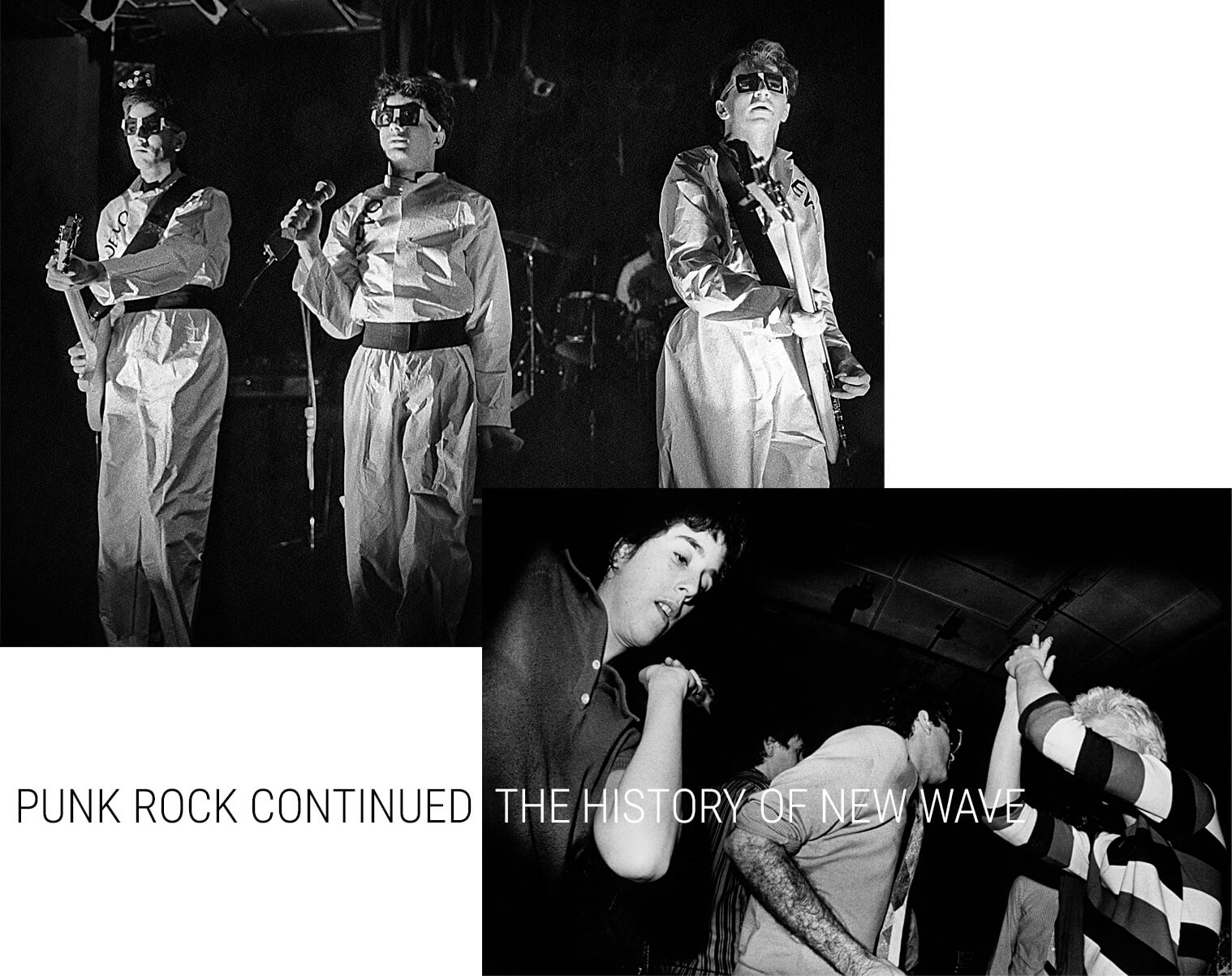

New wave’s metaphorical roots are planted firmly in the soil of punk rock. In fact, there was a brief moment in early to mid 70s when the terms “new wave” and “punk rock” were used almost interchangeably, though the former was more likely to come from the mouths of music critics while the latter was more often embraced by musicians.

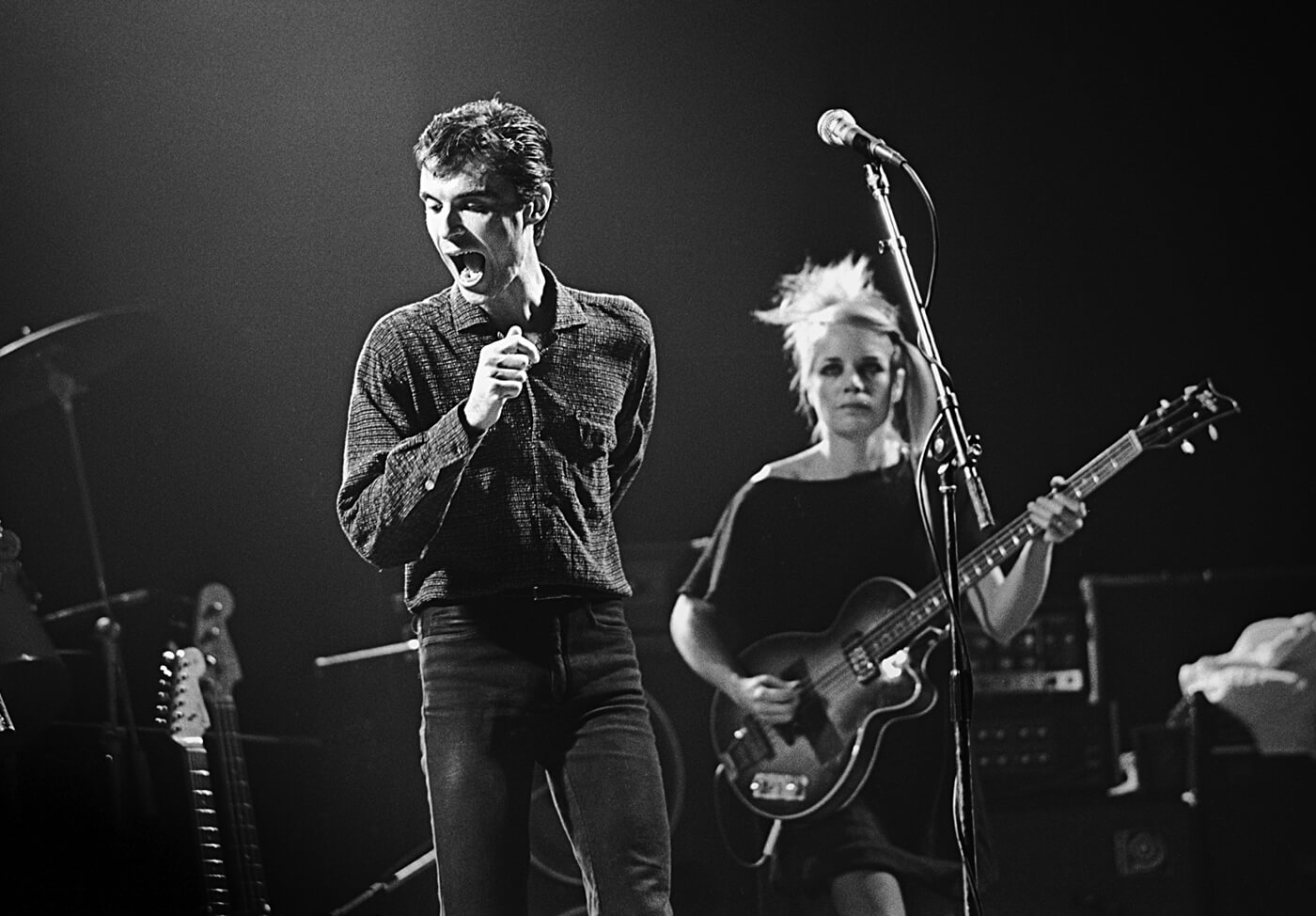

At the tail end of punk rock’s heyday in the late 1970s, the sonic differences between these two genres began to crystallize. Bands that cut their teeth in the belly of the punk rock scene, like Blondie and The Talking Heads, strayed further and further from the aural stylings of their punk rock contemporaries and found themselves sailing in the uncharted waters of new wave.

Where punk rock was raw and raucous, new wave was bright and euphonic. Where punk rock was angry and abrasive, new wave was quirky and clever. While many new wave artists held onto parts of the punk rock ethos (remaining decidedly anti-establishment and anti-corporate) their music tended to be less political and less anarchistic than most punk rock.

All of these factors, when combined, led to one huge difference between punk rock and new wave: marketability. While even the most iconic punk rockers seldom enjoyed commercial success (in part by design; anti-capitalism has always been a pillar of punk rock philosophy), new wave artists could chart. In the late 1970s, songs like “Heart of Glass,” by Blondie and “My Sharona,” by The Knack started hitting number one. The era of new wave was officially underway.

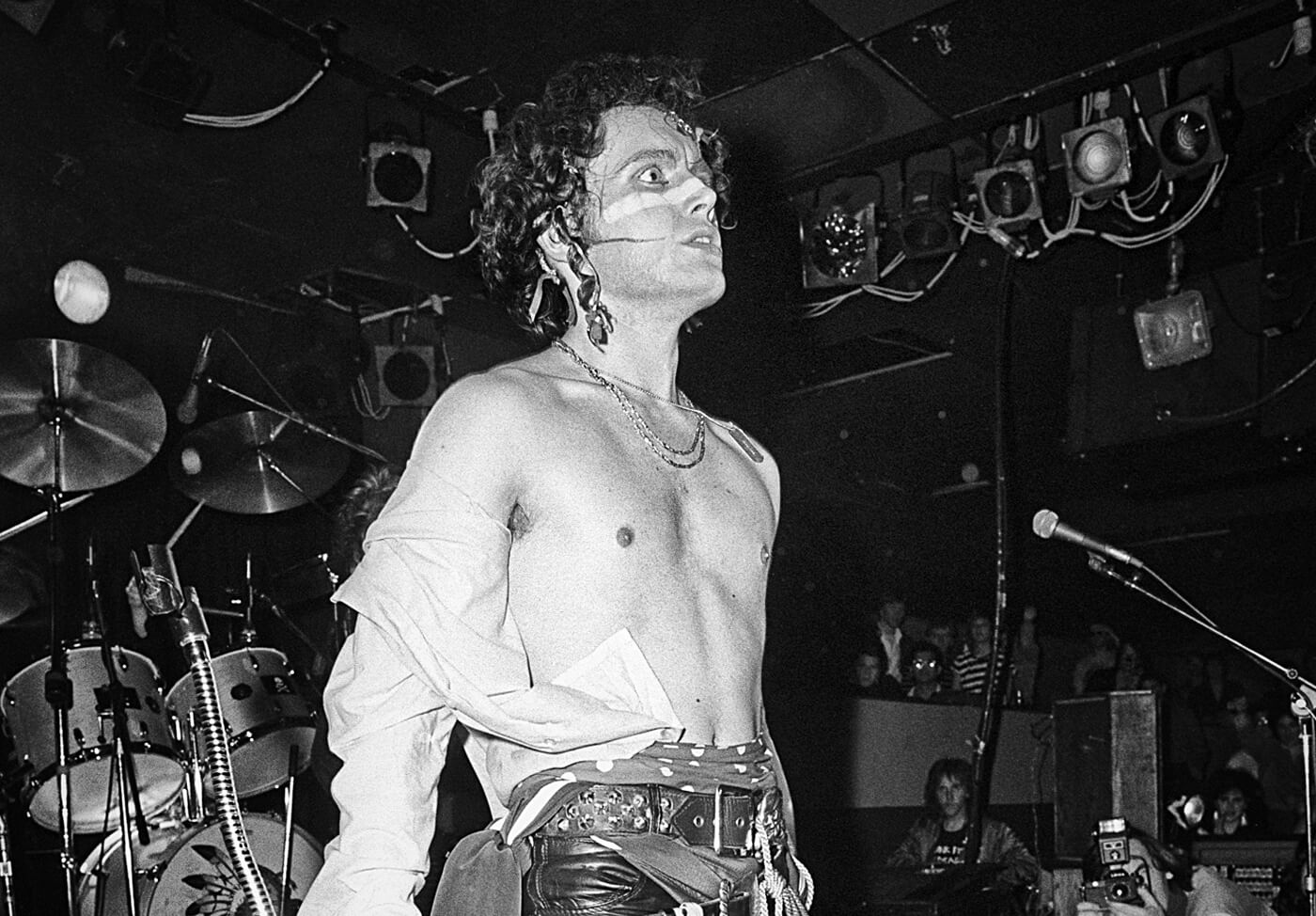

Even as new wave began to take off, the exact characteristics of the genre remained a bit blurry. Bands like Adam and the Ants and Bow Wow Wow became known for their rhythmic experimentation, releasing songs with clear West African, Cuban, and Jamaican influences. Devo leaned into futuristic sci-fi aesthetics. The B-52s infused their music with humor and camp. As a rule, artists who were labelled “new wave” refused to be pigeon-holed.

However, as the 70s gave way to the 80s, one uniting element became more and more ubiquitous within the new wave movement: the synthesizer. The previously undefinable genre of new wave now had a distinct sound, and it was absolutely electric. As the popularity of new wave reached new heights, the strange and sonorous sound of the synth became the most notable leitmotif of the decade.

New wave peaked in the early 80s, then began to recede into the cultural background, though not without making its mark on the musical landscape. Before fading from the radio, new wave managed to inspire the birth of synth-pop — a genre that would define an entire musical era.

Despite the fact that new wave has lived well outside of the zeitgeist for years now, it still enjoys occasional bursts of relevance; though it seems many have forgotten that its origins lie in the seedy heart of the 1970s punk rock scene. The likes of Debbie Harry and David Byrne were punk rockers long before they became new wave pioneers. Collective memory sure is a fickle thing.

If you would like to learn more about the history of new wave, check out Michael Grecco’s punk rock coffee table book, “Punk, Post Punk, New Wave: Onstage, Backstage, and In Your Face.” Let Grecco’s photography transport you to the golden age of new wave.